Definisi Fishway

Fishway atau tangga ikan atau jalur ikan adalah gabungan elemen

(struktur, fasilitas, perangkat, operasi pemeliharaan, dan upaya atau tindakan)

yang diperlukan untuk memastikan pergerakan ikan yang aman, tepat waktu, dan

efektif melewati penghalang. Contohnya termasuk, tetapi tidak terbatas pada,

tangga ikan yang dapat diatur, lift

ikan, jalan pintas, perangkat pemandu, zona lintasan, aliran operasional, dan

penghentian suatu unit bangunan.

Istilah "fishway," "fish pass,"

atau "fish passageway" (dan

juga "eelway," "eel pass," atau "eel passageway") dapat

dipertukarkan. Namun, Rekayasa (Engineering)

merekomendasikan penggunaan istilah "fishway"

atau "eelway" karena

istilah tersebut konsisten dengan 16

U.S.C. § 811 (1994), yang berbunyi:

“Bahwa hal-hal yang dapat menjadi ‘tangga

ikan’ berdasarkan pasal 18 untuk tangga ikan yang aman dan tepat waktu di hulu

dan hilir harus dibatasi pada struktur, fasilitas, atau perangkat fisik yang

diperlukan untuk memelihara semua tahap kehidupan ikan tersebut, dan operasi

serta tindakan proyek yang terkait dengan struktur, fasilitas, atau perangkat

tersebut yang diperlukan untuk memastikan efektivitas struktur, fasilitas, atau

perangkat tersebut untuk ikan tersebut.”

Istilah " tangga ikan " atau

" tangga sidat" mengacu pada tindakan, proses, atau ilmu pengetahuan

untuk memindahkan ikan (atau sidat) melewati penghalang aliran sungai, misalnya

bendungan.

Zona Lintasan

Zone of Passage (ZOP) atau zona lintasan tangga ikan harus berada di area yang berdekatan yang berupa bentangan alam, baik lateral, longitudinal, dan vertikal yang cukup luas, di mana kondisi hidraulik dan lingkungannya memadai untuk dipertahankan guna menyediakan lintasan melalui aliran sungai yang dipengaruhi oleh bendungan atau penghalang aliran sungai.

Aman, Tepat Waktu, dan Efektif

Elemen tangga ikan dirancang dan dibangun untuk

menyediakan tangga ikan yang aman, tepat waktu, dan efektif.

Ketiga karakteristik didefinisikan seebagai

berikut :

- Jalur Aman: Pergerakan ikan melalui ZOP harus tidak mengakibatkan stres, cedera , atau kematian ikan (misalnya, karena tarikan turbin, benturan, dan bertambahnya pemangsa atau predator). Jika pergerakan melewati penghalang mengakibatkan kematian atau kondisi fisik yang mengganggu perilaku migrasi, pertumbuhan, atau reproduksi, hal ini tidak boleh dianggap sebagai jalur yang aman untuk tangga ikan.

- Jalur Tepat Waktu: Pergerakan ikan melalui ZOP harus berlangsung tanpa penundaan atau dampak yang signifikan secara material terhadap pola perilaku penting atau persyaratan riwayat hidup ikan.

- Jalur Efektif: Pergerakan target spesies yang melalui ZOP harus menghasilkan keselarasan yang menguntungkan antara desain struktural, operasi dan pemeliharaan, dan kondisi lingkungan selama satu atau beberapa periode utama. Efektivitas mencakup penilaian kualitatif (misalnya, integritas papan penahan kayu, pengaturan waktu siklus hopper) dan pengukuran kuantitatif. Istilah "efisiensi" (dan hiponimnya yaitu efisiensi lintasan dan efisiensi tarikan) dicadangkan untuk elemen kuantitatif efektivitas.

= Efisiensi: Ukuran kuantitatif dari proporsi populasi yang termotivasi untuk melewati penghalang (yaitu, populasi yang termotivasi) yang berhasil bergerak melalui seluruh ZOP; biasanya dinyatakan sebagai produk dari efisiensi tarikan dan lintasan.

= Efisiensi Tarikan: Ukuran proporsi populasi (yang termotivasi) yang berhasil tertarik ke jalur ikan; biasanya diukur sebagai persentase dari populasi termotivasi yang menemukan dan memasuki jalur ikan.

= Efisiensi Lintasan: Ukuran proporsi ikan yang memasuki jalur ikan yang juga berhasil melewati jalur ikan; keberhasilan melewati jalur ikan biasanya diukur di pintu keluar jalur ikan; juga disebut sebagai "efisiensi jalur ikan internal."

Sumber United States Fish and Wildlife Service Region 5 FISH PASSAGE ENGINEERING DESIGN CRITERIA, Juni 2019, Manual ini menggantikan semua edisi sebelumnya dari Fish Passage Engineering Design Criteria yang diterbitkan oleh U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 5)

Fish swimming performance database

and analyses

Fish swimming performance database

and analyses

Fish swimming speed

Swimming speeds in fish

1

Swimming speeds in fish

2

Swimming speed in underwater

Swimspeeds and energy use of

upriver-migrating

Observations on the swimming speeds

of fish

Swimming speed performance

Scaling thetail beat frequency and

swimming speed in underwater undulatory swimming

A Method for Estimating the Velocity …. Swimming Fish

Swim Performance Online Tools

Swim Speed & Swim Time Tool

Fluid Mechanics of Fish Swimming

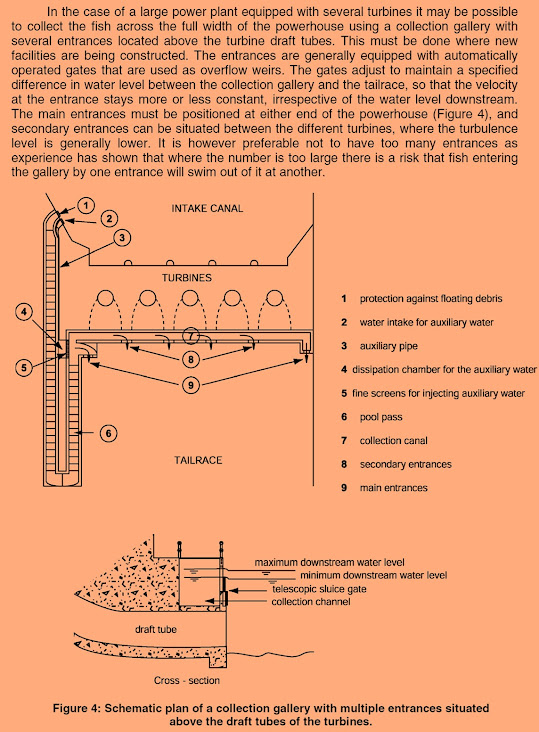

Downstream Fish Passage Facilities

Migration dynamics simulation of migratory fish in rivers

Designing

artificial roughness

in a water channel involves strategically creating surface irregularities to

modify flow characteristics. This is often done to reduce velocity, increase

mixing, or improve heat transfer. The design process typically involves

selecting appropriate roughness elements, determining their size, shape, and

spacing, and considering the impact on the overall hydraulic performance of the

channel.

Here's a more detailed breakdown of

the design process:

1. Defining the Purpose and Objectives:

Artificial roughness can be used to decrease water velocity, which is helpful in areas where high velocities can cause erosion or damage.

Introducing roughness can improve mixing of the water, which can be beneficial for certain processes like heat transfer or aeration.

Roughness can enhance heat transfer by increasing the surface area and disrupting the boundary layer, leading to more efficient heat transfer in solar collectors or other applications.

The design must be tailored to the specific application. For instance, a stilling basin requires a different roughness design than a solar air collector.

2. Choosing Roughness Elements:

Artificial roughness can take many forms, including granular roughness (e.g., stones, pebbles), discrete roughness elements (e.g., cubes, plates), or geometric features (e.g., corrugations, fins).

The roughness elements should be made of durable materials that are resistant to water flow and erosion.

The shape and size of the roughness elements will affect their impact on flow. For example, cubic roughness elements will behave differently than T-shaped roughness elements.

3. Determining Roughness Size and Spacing:

This refers to the height of the roughness elements relative to the channel bed.

The distance between the roughness elements can be expressed in terms of the roughness height (e/s) or the hydraulic radius (R/s).

Different spacing configurations can affect the flow regime, with different spacing ratios leading to different hydraulic behaviors.

4. Hydraulic Calculations and Modeling:

This equation can be used to estimate the flow velocity and discharge in the channel with artificial roughness.

These dimensionless numbers can be used to characterize the flow regime and determine whether it is laminar or turbulent.

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) Simulations:

CFD can provide detailed simulations of flow behavior over artificial roughness, allowing for a more precise design.

5. Experimental Validation:

Conducting laboratory experiments with scaled models can help validate the design and refine the roughness parameters.

Full-scale field testing can be used to verify the design and assess its performance in real-world conditions.

6. Optimization and Refinement:

The design process can be iterative, with adjustments made based on experimental results and simulations.

In some cases, it may be necessary to optimize the design based on multiple objectives, such as minimizing erosion and maximizing heat transfer.

7. Specific Considerations:

Stilling basins require a careful design of artificial roughness to dissipate energy and prevent erosion.

Artificial roughness can be used to enhance heat transfer in solar air collectors, with different roughness geometries leading to different performance.

By carefully considering these factors and using appropriate design tools, it's possible to create artificial roughness that effectively modifies flow characteristics in water channels for various applications.

Calculating bed load transport in steep boulder bed channels

Experimental study of the energy dissipation on rough ramps

An experimental study: effects of boulder placement on hydraulic metrics of instream habitat complexity

The hydraulics of a vertical slot fishway: A case study on the multi-species Vianney-Legendre fishway in Quebec, Canada

Hydraulics of the Vianney‐Legendre vertical slot fishway near St. Ours, Quebec

Hydraulics analysis of rock ramp fishway

Hydraulic of rock-ramp fishway with lateral slope

Hydraulic Analysis of a Novel Fish Passage-Way

The Case of the Miyanaka Intake Dam in Japan

Fish Passes Design, Dimensions and Monitoring

Fish Passes Design, Dimensions and Monitoring

Fish Pass Design for Eel and Elver

Desing of Fishways & Others Fish Facilities

Introduction to Fishway Design

Fishway design toolkits

From sea to source

Fish friendly Irrigation

Taku Masumoto

Design of upstream fish passage systems

The importance of design in river fishways

Pool Fishways, Pre-Barrages and Natural Bypass Channels

Sabo dam

Groundsill K. Opak

HEC-RAS for Vertical Slot Fishway

The completed HEC-RAS

example model can be downloaded by clicking on the below button.

Download HEC-RAS Fish Ladder Model

Tags: Fish Ladders, Fish Passage, Fishways, HEC-RAS, HEC-RAS tutorial, StreamStats

Calculate the energy dissipation of a fish against turbulent flow (W/m3)

To calculate the energy dissipation of a fish against turbulent flow (in W/m³), you need to determine the rate at which kinetic energy is converted into heat due to turbulent friction. This can be estimated by analyzing the turbulent flow field and applying the principles of energy conservation. The dissipation rate, often denoted by ε (epsilon), represents the energy loss per unit mass and time.

Here's a breakdown of the process

and relevant concepts:

Understanding Energy Dissipation in

Turbulent Flow:

Turbulence is characterized by

chaotic, swirling motions of fluid.

These swirling motions create shearstresses within the fluid, leading to energy transfer and dissipation.

The energy dissipation rate (ε)

quantifies how quickly this kinetic energy is converted into heat.

In the context of fish swimming,this energy dissipation represents the force the fish needs to overcome to

navigate turbulent waters.

Key Parameters and Calculations:

Turbulent Kinetic Energy (TKE):

TKE (k) is the kinetic energy associated with the turbulent fluctuations, calculated as k = 1/2 (u'^2 + v'^2 + w'^2), where u', v', and w' are the fluctuating velocity components in x, y, and z directions, respectively.

Dissipation Rate (ε):

The dissipation rate can be estimated from TKE and the turbulent length scale (L) using the formula ε ≈ (k^(3/2))/L, according to some researchers.

Volumetric Dissipation Rate (E):

To get the energy dissipation in

W/m³, you need to multiply the dissipation rate (ε) by the fluid density (ρ): E

= ρ * ε.

Experimental Measurement:

Measuring the velocity field

(instantaneous and average velocities) and using it to calculate TKE and

subsequently ε is crucial, says a study on turbulent flow.

Practical

Considerations for Fish Swimming:

Fish

Swimming Speed and Behavior:

The fish's swimming speed and how it

interacts with the turbulent flow structures (vortices, etc.) will influence

the energy it needs to expend.

Fish Body

Shape and Propulsive Efficiency:

The fish's body shape, fin

movements, and how efficiently it propels itself through the water also play a

role in energy expenditure.

Fishway

Design:

Fishways (structures designed to

help fish migrate upstream) are designed with specific energy dissipation

limits to ensure fish can navigate them successfully.

Example:

Let's say you're studying a fishway

with a volumetric energy dissipation rate of 200 W/m³. This means that for

every cubic meter of water in the fishway, 200 Joules of energy are being

dissipated as heat per second. If a fish is swimming in this area, it needs to

expend energy to overcome this dissipation.

Fishway software

Operating Software for Fishway

Breakdown of the process and example calculations using Excel

Here's a breakdown of the process and example calculations using Excel:

1. Define Design Parameters:

· Target Fish Species: Different fish species have varying swimming capabilities (speed, burst speed, and stamina) which influence the required flow velocity and turbulence within the fishway.

· Flow Rate (Q): The range of discharge the fishway needs to accommodate.

· Slope (S): The overall slope of the fishway, which influences the water flow velocity.

· Pool Length (L): The distance between slots, typically 3-7 times the slot width.

· Slot Width (b): The opening through which water flows between pools.

· Pool Width (W): The width of each pool.

· Number of Pools: Determined by the total head difference the fishway needs to overcome.

2. Key Equations for Design:

· Discharge (Q) through the Slot: A common formula is: Q = C * b * h * √(2 * g * h),

where:

C is a discharge coefficient (typically around 0.65 for vertical slots).

b is the slot width.

h is the water depth at the slot.

g is the acceleration due to gravity.

· Velocity (V) in the Slot: V = Q / (b * h).

· Energy Dissipation (ΔE) per Pool: ΔE = ρ * g * Q * S * L,

whee:

ρ is the density of water.

g is the acceleration due to gravity.

S is the slope.

L is the pool length.

3. Example Excel Sheet Setup:

· Input Parameters:

Create columns for the parameters you defined above (e.g., Target Fish Species, Q, S, L, b, W, Number of Pools).

· Calculations:

- Water Depth at Slot (h): You might need an iterative approach or a simplified method based on empirical relationships to estimate 'h' initially, and refine it as you iterate through the calculations.

- Discharge (Q): Use the formula Q = C * b * h * √(2 * g * h).

- Velocity (V): Calculate V = Q / (b * h).

- Energy Dissipation (ΔE): Calculate using the formula ΔE = ρ * g * Q * S * L.

- Check Velocity Limits: Ensure the calculated velocities stay within the acceptable range for your target fish species.

- Check Energy Dissipation: Ensure the energy dissipation is within acceptable limits for each pool.